When I read that SCI-Arc was hosting a symposium on the topic of AI and design, naturally, I was very intrigued. Not that long ago, I had been enrolled and teaching at this school with foci on the topics of computational and algorithmic design, and my 2006 thesis employed AI and evolutionary algorithms to make space and architecture. This seemed like a natural fit. Sadly, it didn’t live up to the hype.

It was planned to be a 4-hour symposium, so it would take a good deal of scheduling to make this work. Organizing back-to-back babysitters, shuffling current orders, and setting up the SLS printer for a long job preoccupied the early part of my day, which coincidentally was rainy and made traffic terrible. Eventually, I got to SCI-Arc about 20 minutes before the start.

It had been a few years since the last time I had visited this place. Not much has changed, except for the number of students. I bet there are 50% more kids here. Gotta keep pumping up those enrollment numbers. Those are rookie numbers.

I also forgot the golden rule of SCI-arc. This shit is going to be late. So getting there 20 minutes early was a dumb idea. I could’ve strolled in at 7:15 and not missed much. So I got to reminisce on how much my ass hurts in these folding chairs. I can recall sleeping though many lectures in these chairs. And a few kids sleeping through my lectures. Circle of life.

While I had a couple hours to kill, I meandered around the studios. Saw a few professors I knew, saw a few I didn’t recognize. Everyone’s a bit older and grayer. Everyone still dresses like a hipster mortician.

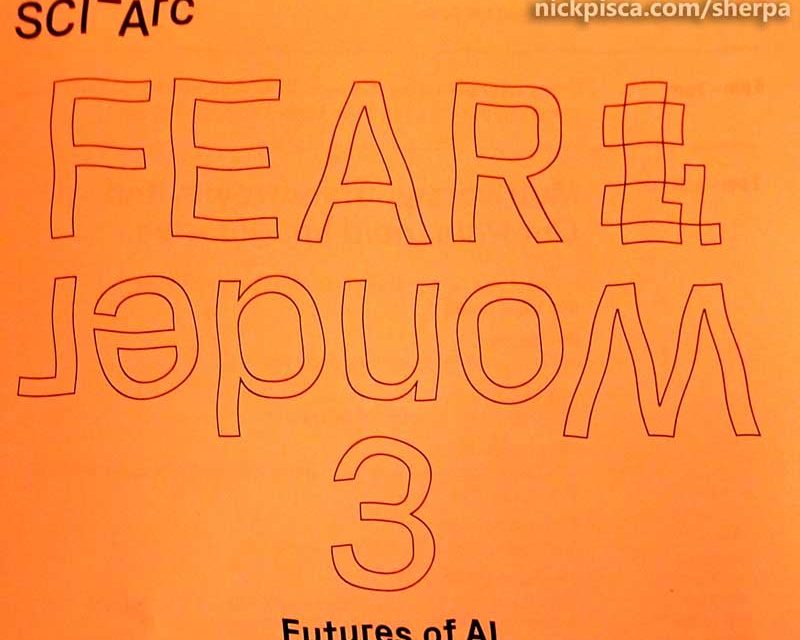

I noticed nearly every desk has their own 3D printer. Most are those cheapo reel printers, but that’s still cool. Most of the students models are not end-use, and for modeling representation, so more power too them. I talked to a few students and they said it costs too much to use the school’s 3D Printers, so they just buy their own.

I remember the when this place got its first starch printer. The damn thing broke down so much, I remember having to help fix it. Now these things are so stable, most students just set up jobs and go to their classes. I saw about every third printer making something.

While I’m thrilled the everyone has access to these machines, I was a little disappointed on the geometric output. Pretty much everything I saw being printed or had been printed, was something that could have just been made in a wood shop with conventional saws and tools. Probably at a fraction of the price in a fraction of the time required. Not a lot of innovation, but I guess that would come with more experience with the machine. The school was supposed to be built on a foundation of “making,” yet if the students can’t distinguish between what are the appropriate tools for that particular design, then what’s the point?

Which is a good segue into the symposium.

They finally opened up the great whale sarcophagus and found our seats. The place was quite packed in the beginning. There were supposed to be some print signings and drinks, but I didn’t indulge. Let the kiddos have all that stuff.

They finally opened up the great whale sarcophagus and found our seats. The place was quite packed in the beginning. There were supposed to be some print signings and drinks, but I didn’t indulge. Let the kiddos have all that stuff.

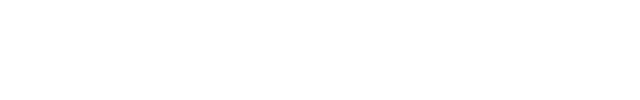

Some backstory. This symposium was originally titled something like the “Future of Automation.” I remember, because it was sent out on the SCI-Arc newsletter some months prior. Only in the last couple weeks did the title, topic, and attendees mutate into the form shown on the right.

That didn’t deter me from attending. I’m qualified to speak on both, but if I had to drill down on my primary focus, I would call it automation. Like Ross Goodwin would say in his presentation, the public perception of AI is a “moving goalpost,” so AI (or machine-learning as the current iteration of shifting definitions) would always be a subset of that category. It was a bit confounding on why the curator decided to narrow the intended conversation to AI per se, when as what will be shown in the text below, the vast majority of presenters didn’t have direct experience with the implementation or design of AI-type programming, and most of their work was based on the palatable perception of AI interaction or the use of automation systems, hardware or software.

Hernan Diaz Alonso, Director of SCI-arc, introduced the curator, Liam Young. Young runs the EDGE MS Fiction and Entertainment Program, and judging by Hernan’s tepid statement, I’m not sure if he that invested in this symposium. He kept yammering on about how “these stories” are important. Already, I had a sinking feeling this conference was going to diverge far from the built environment and cinema.

Liam had a prepared script to dramatize his introduction of the speakers. He obviously wanted to immerse us in a futuristic world, eliciting and citing Bladerunner as a launch pad for the upcoming three hour ride.

You kind of had to be there to experience this preface. It was pretty audacious. It was so floral and complicated, that as Liam switched over to introduce the first speaker, George Hull (below), George started off his lecture saying, “I have no idea what Liam said, but it sounded smart.” Ahh, memories of SCI-arc… where specificity and detail are overshadowed by linguistic abuse. Never change.

In hindsight, I wish Liam had reversed the order of speakers. He had George Hull, Jon Carlos, and Victor Martinez (all concept artists working in the film industry) speak at the beginning or middle, while some of the more technical speakers were at the end. It would have made more sense to get the assessment of the current state of computational AI-systems, as conducted by the speakers from Microsoft, Google, and other smaller digital firms, and then showcase the cinematic and design potential for engineering the form and composition and interaction with future AI interfaces.

In hindsight, I wish Liam had reversed the order of speakers. He had George Hull, Jon Carlos, and Victor Martinez (all concept artists working in the film industry) speak at the beginning or middle, while some of the more technical speakers were at the end. It would have made more sense to get the assessment of the current state of computational AI-systems, as conducted by the speakers from Microsoft, Google, and other smaller digital firms, and then showcase the cinematic and design potential for engineering the form and composition and interaction with future AI interfaces.

Hull, and Carlos (right), explained their practices and history in their respective lectures. Hull made a classic mistake of dwelling on his passed, instead of staying on topic. He clearly had an impressive concept art reel, and all he had to do was lean on that. The lengthy introduction of his past just detracted from his presentation. After a string of beautiful automotive renderings, he made an odd assertion. He was a proponent of “form follows function,” and the “[movie] script is the function.” Probably not the right aphorism for speaking at a school of architecture, and especially not the right idiom when examining his designs. There is no doubt he has exceptional talent, but to post-process his obvious stylism as more than just stylism is a bit disingenuous.

This clash with the contents of his lecture and his stylism occurred again when he described a connection to natural Darwinism to “non-design.” He espoused his love of purely engineered designs, devoid of aesthetic interference, and later posited whether AI would veer toward the functional versus the stylistic. Once again, this seemed like a convoluted way to shoehorn AI into his portfolio for the presentation. He even collected a taxonomy of geometries and “plotted” them in a makeshift graph on axes of “smooth” versus “hard,” and “simple” versus “complex.”

What’s confounding about this is, there are already designers working with automation that employ AI, recursive, evolutionary, and emergent coding to explore these formal and geometric options, notably the Undersexualized Recursion project, and others. This work is implemented in a structured and regimented way, and in no way is it conjecture or theory. The use of automation to explore these configuration is already a trivial task, given the access to modeling software, scripting, and processing.

Jon Carlos, the Supervising Art Director of the television show Westworld, kicked off his lecture with playing the preview of the second season. Not having HBO, I haven’t watched any of this show, but I have read about it online occasionally. The preview didn’t really explain anything noteworthy about AI, in fact it was rather elusive for anyone not familiar with the show. We get it. It’s dramatic android shit.

But he moved on to more aspects to the show, and for the duration of his lecture, he treated the show kind of like it was basically a real thing. He showed a slide delineating the “Core Divisions” of the amusement park, containing the process of the android maintenance. He explained how different settings required different color palettes. He showcased the complicated process of synthetic plastic printing and biologically-printed prostheses for constructing the androids. He even cited a quote explaining the transition from “repairing mechanical versions” to bioengineered androids as a cost saving measure “at the cost of their humanity.” Where I get confused on this preface is precisely where AI comes into this. In the next slide, he even displays the 3d-printed mini leather jacket, grown from cells, as if to bolster his argument. While the visuals and descriptions he’s providing are interesting nonetheless, but biological printing, color schemes, and composite construction are not inherently emblematic of AI.

Later he cautiously explains the next season in the show, where they apparently download “source code” of theme park participants without permission for corporate financial gain. As not a fan of the show, I really didn’t have an opinion on that, or why it pertained to the symposium. Carlos did try to mix this topic with some deterministic theory, and I was reminded of Sam Harris’ discussion on how to test if AI was trying to be nefarious, by connecting it to a false internet and monitor the data transfer to ensure isolation.

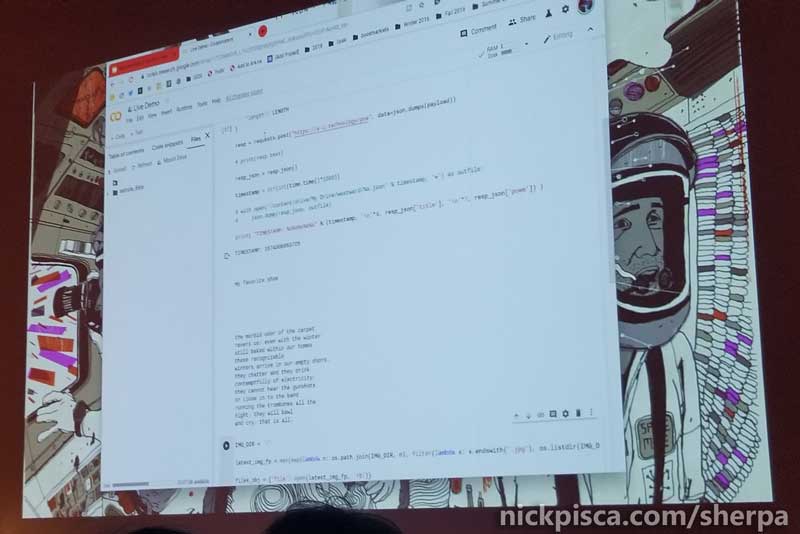

Next up was a programmer named Ross Goodwin, who presented some actual codes and did a live demo. Anyone who has worked in Computational Design knows how risky it is to conduct a live demonstration, because anything can fail at any time. So I have to give Ross some major credit for implementing two of his projects in real time.

Right off from the bat, Ross caveats his lecture decreeing this is “AI as it exists now” with hand air quotes, and follows it with a clarification: “AI is [more] machine learning.” It was a very diplomatic transition from the speculative work from the previous speakers to his more tactile utilization of current AI or automation techniques.

The first example was his poem generator. He simply contributed crowd-sourced description and title strings, and utilized google neural networking to generate a short poem. It had a Lewis Carroll vibe, a bit surreal, but not entirely random. Ross even encouraged the audience to “not underestimate randomness,” which is an apt statement when dealing with evolutionary or breeding algorithms and recursion.

This poem, generated based on feet or something, only took a few moments to appear.

This poem, generated based on feet or something, only took a few moments to appear.

Ross admits that he merely used neural networks and does not manipulate or invent them. He tries to “instrumentalize” them. He also collaborates on sculptures and architecture to venue his AI poetry in real time. With some of Ross’s work, I’m reminded of the “Poème électronique” in 1958 combining the talents of Edgard Varèse and Le Corbusier. In Goodwin’s Trafalgar Square project, he confessed he implemented several vulgarity provisions to prevent the poetry from generating inappropriate content, which I found to be a bit parental and not letting the AI manage that on its own.

While Ross’ work is pretty impressive, the technical aspects were pretty average. Between breaks, I chatted with my neighbors. Two of them happened to be programmers, like me, and we remarked on how comical the poetry was, but the actual coding wasn’t that difficult. If the destination is to make quirky silly poetry and prose, then mission accomplished; it’s not that far fetched to amalgamate random strings into a semi-intelligible paragraph. Where the true complexity with AI will be where the software begins to understand the context (not just guess) and properly structure it. With Ross’ current experience and portfolio, I’m sure he’s on track to achieving that.

Dominic Polcino, Animation Director of Rick and Morty, presented probably the most lackluster conversations of the evening. I’m quite confident he’s a wonderful animator and writer, but he has no interest in AI. While Liam prodded him to take a stand on the comedic animation of AI in the cartoon, Dominic was pretty reluctant to express how he came about his aesthetics. His primary focus was jokes, not accurate representation of artificial intelligence.

The clip projected for the audience (shown below) lampoons one of the most classic examples, and most heavily discussed topics, of AI morality with automobiles. You can’t swing a schrodinger cat in a room full of AI philosophers without hitting someone talking about autonomous cars and the moral decision-making going on in that programming.

So for Dominic to be reticent on this is kind of odd. It’s almost as if he and the show just make a cursory examination of the pitfalls of AI and cars, and just tossed together jokes, without truly examining the repercussions. And to be honest, I don’t really care. If that’s his prerogative, more power to him. The room was erupting with laughter, so he won. But this clip and his presence on the panel was a bit out of place.

Next to Dominic was the Director of USC’s Mixed Reality Lab and founder of Vrai Pictures, Jessica Brillhart. Along with Goodwin, I found Brillhart’s comments to be the most illuminating.

Brillhart kept her visual aides to a minimum, and proceeded to explain how she implements VR in a gaming and/or cinematic way. Liam spent a good part of the conversation trying to steer her toward the topic of orienting the viewer, which I, and I detect Jessica, found a bit annoying. I think a younger generation of viewers have developed a successful behavior while in immersive gaming or virtual environments that don’t require obvious reorientation, except in major elements of the plot or narrative. For older people still reliant on the archaic directorial role of “framing” the viewer, VR must be a bit disconcerting.

Since she was derailed by the topic of framing and orientation, most of her comments on AI came at the end. In almost a perfect and succinct analysis of the previous (and upcoming) presentations, she critiqued the premise, saying that rehashing the “same aesthetics and same tropes” was redundant, and that AI would become part of “underlying infrastructure of the world,” instead of a visual component. Yes!

Next was a presenter not on the itinerary. Former SCI-Arc alumni, Victor Martinez (below), showcased some of his stylistic cinematic robots and machines.

He was very much in the same vein as Hull and Carlos, proposing stylistic proposals for upcoming and former film projects. While these three artists are really impressive, their work is tangentially based on AI, and in a lot of the conversations, mentioning artificial intelligence seemed forced into the portfolio.

He was very much in the same vein as Hull and Carlos, proposing stylistic proposals for upcoming and former film projects. While these three artists are really impressive, their work is tangentially based on AI, and in a lot of the conversations, mentioning artificial intelligence seemed forced into the portfolio.

The symposium was running late, in true SCI-arc fashion, so they took a SCI-arc break. Five minutes = 17 minutes in SCI-arc world. Lauren McCarthy (right) kicked off after the pause with her artist social media experiments.

She invented the so-called “creepiest social network” called Follower, where she surveils a person for a day. Also, she made other experiment where she basically became a human Alexa in willing-participants’ homes. She critiques ubiquitous surveillance with her performance art and programming, but has a strong social justice bias in her lecture. At one point she attempted to claim that automation in the home would most negatively affect women and their roles in the family. First off, implying that the home is the women’s domain is odd. Second, how is this different than the industrial improvements to homemaking with the advent of the mechanical dishwasher, washing machine, and other appliances? Third, later in the lecture, she cited the reluctance of monitoring companies from reporting crimes “against women” as a negative, even though earlier she implied the devices’ presences were a nuisance and/or intrusion. Regardless of these inconsistencies, none of this had anything to do with AI.

Continuing down the social justice spiral, we were introduced to the former Architect of Microsoft’s Cortana personality, Deborah Harrison. Right away, gender dominated the conversation. Even though she admits that Cortana was based on a personal assistant, the symposium derailed on all sorts of irrelevant human-based issues. For a truly new AI-type of assistant, why does the unit need a gender? It doesn’t have a human form, no human desires, no human needs, no human genitals. All of this anthropomorphizing was a complete non sequitur.

The hang up for Harrison is probably because she, as she said in the interview, thinks “conversation is inherently emotional.” Between humans, I’d agree, however, having a conversation with Cortana or Alexa is about as stimulating to me as me talking to my TI-89. It takes in inputs and outputs stuff. That’s it. Which makes it so hard to take her next statements seriously at all. She wanted to implement a parental “wrist-slap” against humans that talk naughty to the device. Ooof. Thankfully, that wasn’t programmed into the software, and she wanted “Cortana to be positive and kind.” Well, that should be a no brainer if you want to sell these things.

Harrison represented a very top-down methodology at Microsoft, where they were actively trying to control the AI learning process with all sorts of nanny rules to regulate the user. They even spent weeks trying to come up with proper response to “I’m gay,” when a group of kids came up with the currently-proper PC reaction. Microsoft is not using this technology and intelligence to their advantage at all. They have AI just sitting there and all the programmers in their company to aide them in their computational design process, and they choose to actively work on the most mundane of ways to restrict the machine: human design intervention.

The last speakers I saw were Veronica So and Siddhart Suri. It was getting well passed the planned end time of the conference, so I left during Suri’s lecture. Veronica collaborates with another person to make the digital organism BOB (right). This piece reminds me of the collaboration I had with Matter Management (Juan Azulay) and his Vivarium project. Using a feedback loop from physical organisms, I developed an topologically-variable digital organism that grew and changed based on various parameters returned into the physical environment. It was showcased at the SCI-Arc gallery in 2010. BOB is clearly more visually-advanced, probably due to the improved technology available over the last decade.

The last speakers I saw were Veronica So and Siddhart Suri. It was getting well passed the planned end time of the conference, so I left during Suri’s lecture. Veronica collaborates with another person to make the digital organism BOB (right). This piece reminds me of the collaboration I had with Matter Management (Juan Azulay) and his Vivarium project. Using a feedback loop from physical organisms, I developed an topologically-variable digital organism that grew and changed based on various parameters returned into the physical environment. It was showcased at the SCI-Arc gallery in 2010. BOB is clearly more visually-advanced, probably due to the improved technology available over the last decade.

Veronica So compared her work to Sims (I would argue NPC’s), but her first iteration of the project was, in my opinion, better than the second. I think it was more raw and less palatable. The second version is trying hard to appeal to the user, giving it recognizable mobility and anatomy. Perhaps the best AI representation would end up being something completely formally and aesthetically unrecognizable. Given a near boundless searchspace, I would amend my previous sentence to remove the word “perhaps.”

The biggest problem for these aesthetic representations are they don’t at all discuss the “Intelligence Explosion,” from the actual genesis of Artificial Intelligence. They treat these stylistic representations of AI as a static formulation, when in reality, a machine capable of self-modification would be processing new ways to reconfigure and reprogram itself at an exponential rate. Drafting up stylistic variations might be a fun thing, but the dynamic rate of artificial intelligent growth would render any rendering irrelevant.

Jessica Brillhart’s criticism disrupts the whole premise of the symposium. AI isn’t an aesthetic or a style. At best, it becomes an infrastructural and ubiquitous element of society, at worst, it recursively regenerates itself so quickly, that it’s physical formulation will be in a constant state of flux, if it ever renders and actualizes itself in a physical form.

I was hoping for this conversation to move toward why and how AI would interact with humans, and how the parameters of resources and energy would limit the generative actualization of AI. That would be an interesting feedback loop to discuss or explore. Given a finite set of PHYSICAL resources and energy, but a near infinite set of DIGITAL processing resources, how would the form evolve. That would be the only way a human species could keep up with the processing of a ever-increasing recursively-self-editing AI program. But for the most part, this symposium did not address this, and merely showcased palatable instances of glamorized robotics, 3D Printing, simulations, Virtual reality, and omnipresent surveillance.

“at worst, it recursively regenerates itself so quickly, that it’s physical formulation will be in a constant state of flux, if it ever renders and actualizes itself in a physical form.” Is this measurable, controllable, exploitable? That might mean that there are “ends” associated with the “means”. How human.